Issue Brief - China’s Local Government Financing Vehicles Face Debt Repayment Challenges, Impacting Broader Economic Stability

An in-depth look at geopolitical and economic trends

By: Kristina Honour

Welcome back to the TSG Issue Brief, where we take an in-depth look at geopolitical and economic trends. This piece unpacks the interconnected issues of China’s property crisis and local government debt.

Editorial Note: In the last month, the Chinese government has proposed new policies to address the property crisis discussed in the piece below. These measures include easing restrictions for first-time homebuyers, lowering down payment thresholds and minimum mortgage rates, allowing purchase of multiple properties, and creating a $42 billion People’s Bank of China-funded facility to fund bank loans for state companies to buy up housing stock. An earlier plan called for funding developers to ensure that they finish existing properties. Many economists believe that while this might increase cash flow to developers, the amount allocated by the PBOC is not sufficient to buy up the bulk of unwanted property, and the properties may not be attractive even at reduced prices. Local governments, once dependent on revenues from a burgeoning property market to underwrite infrastructure projects and unfunded central government mandates, need to find new sources of revenue. It is likely that if the decline in new home sales continues in coming months, developers and construction companies will see continued solvency problems and default further on loans. This crisis, years in the making, will take years to resolve.

China’s economic growth has not rebounded in the aftermath of COVID-19, dragged down by a post-lockdown decline of consumer confidence, an emphasis on personal saving to meet the next crisis, a struggling real estate sector, and a ramped-up deleveraging campaign of local government debt by the central government. At the March Two Sessions meeting, concerns were raised that Local Government Financing Vehicles (LGFVs) are heavily reliant on land sales to meet debt obligations, which surged to $9.2 trillion in 2024. LGFV debt accumulation poses a threat to economic stability.

Why do LGFVs matter?

China’s decentralized local government financing mechanism, LGFVs, have rapidly accumulated debt due to the economic slowdown and drop in property sale revenues. Local governments are tasked with providing most social services, including infrastructure development, but the central government controls most of the tax revenue, transferring funds to local governments to help them meet their needs. Local governments are under pressure as they are judged by the central government on their ability to provide adequate services, follow the center’s initiatives (particularly security and economic mandates), and promote local economic growth. To supplement insufficient transfers, local governments accumulate additional revenue through LGFVs to fund their projects. This distorted funding structure encourages local governments to run large deficits in pursuit of ambitious development goals such as infrastructure projects, and to comply with key unfunded mandates from the central government: affordable housing, urban village upgrading, construction of emergency facilities. The central government is concerned about risk exposure as looming LGFV debt payments may not be adequately covered by the government budget and land revenue. These debt concerns not only raise questions about the sustainability of local government finances but also impact investor and foreign direct investment (FDI) confidence in China's economy, particularly amid its struggles with attracting FDI and achieving robust growth.

Beijing’s response to growing LGFV debt risk

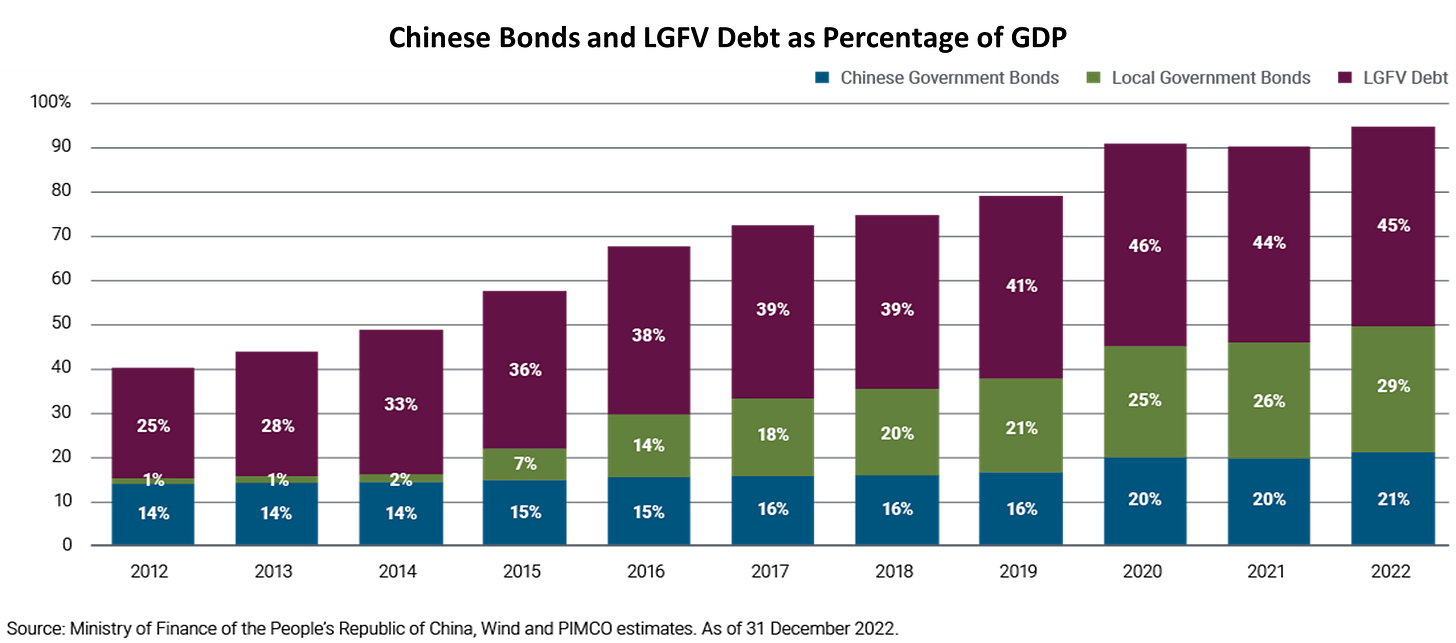

Total LGFV debt represents around 45% of China's GDP. The central government began tightening control over LGFVs in 2021 to mitigate risk from rapidly expanding debts.

The importance of managing local government debt and controlling additional debt issuance was emphasized by leaders at the April 2023 Politburo meeting, heightened by central bank concerns that they will be responsible for bailing local governments from their debt burdens.

In the July 2023 Politburo meeting on the economy, Beijing revealed they will put forth a "basket of measures" to diffuse LGFV risks. The specifics of this basket have still not been announced, but the Ministry of Finance stated “no central bailout” should be expected. Instead, measures will focus on debt rollover: refinancing, bond swaps, and rate cuts. The central government is also targeting housing reform to encourage a rebound of the property market, including easing some borrowing rules and relaxing home purchasing curbs in some cities. These reforms follow President Xi's April 2023 statement that "houses are for living, not for speculation," referring to the conflicts arising from the infamous pre-sale.

With major real estate developers facing liquidation and increased defaults on corporate bonds, both LGFV revenue and debt repayment have come under increased pressure. In January, Beijing began targeting LGFV offshore bonds for new regulations including bank’s use of repayment mechanisms. In March, regulators announced new limitations for regional banks’ standby letter of credit, or SBLC – a pledge by a lender to repay the debt if the issuer cannot. And in April, the central government’s interbank market watchdog NAFMII halted new registration of credit-linked notes that use LGFV offshore debt as underlying assets.

A broad LGFV system collapse is, however, unlikely due to collateralized loans from central policy banks as well as local and central government interest in stability. The central government will likely continue tightening regulation as it navigates a slow real estate market, low investor confidence, and broader perceptions of a slowing and weakening economy.

How did we get here?

Decentralized local government financing in China emerged in the late 1980s after Reform and Opening. The Chinese government originally allowed local governments to develop trust and investment companies (TICs) – entities owned by local governments or enterprises that facilitated funds from both domestic and overseas investors. In the mid-1990s, rapid leveraging by TICs resulted in a wave of defaults (among the most famous was Guangdong International Trust and Investment Company bankruptcy in 1999), but local revenue shortages and desire for officials to promote investment led to the rebirth of TICs as LGFVs. LGFVs act as subsidiaries of local authorities and use local land as collateral to borrow for municipal infrastructure projects.

Since late 2008, LGFVs increased borrowing rapidly, accumulating 11.4 trillion RMB by 2009. By 2012, debt reached 13.5 trillion RMB, 25% of GDP. The composition of LGFVs loans, which are classified as corporate debt, is approximately 60% bank loans, 30% bonds, and 10% other financings. In 2024, 4.65 trillion RMB ($651 billion) worth of LGFV bonds will be due, the highest on record and an increase of 13% from 2023.

The property crisis

Over the past few decades, China has experienced a massive property boom fueled by urbanization, rapid economic growth, and government policies aimed at promoting real estate investment. LGFVs sell land usage rights to property developers, who sell homes to Chinese property buyers on a pre-sale model: developers sell not-yet-completed property to homebuyers, many of whom put down nearly all of the amount of the residence in cash at the time of purchase. This process allows property developers to operate like a shadow bank by using deposits and mortgage payments from homebuyers to invest in additional property development. Housing demand boomed and prices rose, with the expectation that prices would continue to rise.

Regulatory pressure began to change the property market outlook. In August 2020, new regulations – the “Three Red Lines” – required property developers to keep their liabilities at less than 70% of their assets, maintain a debt‐to‐equity ratio of less than 100%, and a ratio of cash to short‐term debt of at least 100%. Banks were also constrained in making loans to developers. While some real estate developers improved their positions short-term, the new regulations had significant downsides, especially on the revenue generating side. According to CRIC, of the 69 major listed real-estate development companies, 35% fell into the “red” category in 2023, up from 20% at the end of 2021.

China’s slowing economic growth, the impact of COVID-19’s strict restrictions, and low consumer confidence present challenges for the real estate sector’s high-risk pre-sale model. Total residential area sold has dropped year-on-year since 2021, down 26.8% in 2022 and 15.1% in the first nine months of 2023. Home sale value is also dropping, with new home prices in March dropping 2.2% from a year earlier (the biggest decline since August 2015). The sluggish real estate market can no longer supply the necessary cash flows for developers and will lead to increased default on corporate bonds. Two of China’s largest real estate developers face liquidation; Evergrande has liabilities of nearly $330 billion, while Country Garden holds $200 billion. In December 2023, Moody’s downgraded the debt of another large developer, Vanke, to Baa3(16) – one step short of a “junk” rating.

The Chinese government implemented several measures to alleviate the property market downturn, including lowering restrictions on down payments and mortgage for second-time homebuyers and instructing state-owned banks to provide debt-payment loans and restructuring. In some provinces, the central government let local governments lift restrictions on housing purchases, even allowing non-residents to purchase housing and then apply for residency in the province.

The property market downturn will likely take years to resolve and has turned off potential buyers from the pre-sale payment model of the 2010s. China's banking sector has made interest rate adjustments for at-risk developers, but housing and commercial real estate prices remain underwater.

Stress on banking sector

China’s slowing property market has adversely affected the banking sector as well. Bank lending to the property market (loans, bonds, and shadow credit) accounts for roughly ⅓ of all lending. Banks began extending and lowering interest rates for loans to at-risk developers in November 2022. Mortgages account for a significant portion of bank liabilities, though high down payment requirements and low default rates among Chinese citizens acts as some level of protection. Given the pre-sale nature of China’s property market, however, default rates may increase if homeowners believe developers will fail to complete the builds.

Property market impacts on LGFVs and local governments

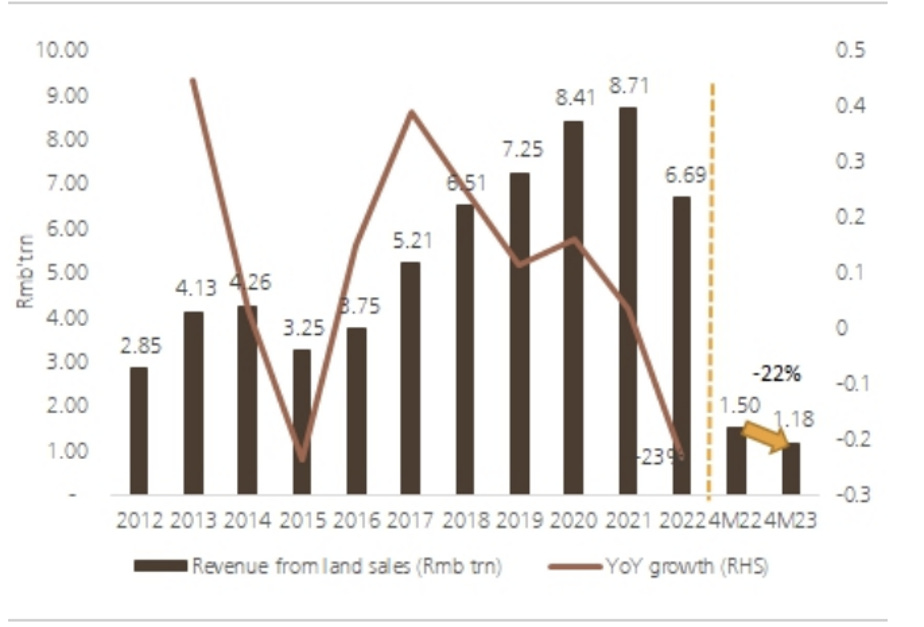

Local government revenue is heavily reliant on land sales to finance investment and development. Land sales to commercial property developers supplement high-cost infrastructure investment by LGFVs, protecting low-revenue projects from straining local budgets. Yet land revenue has been falling, sales revenue dropped by more than 20% in 2022, and about 15% in 2023 to 5.45 trillion RMB. Comparatively, in 2021, China sold 8.7 trillion RMB in land. As land value continues to fall, questions on whether LGFVs can cover their monthly debt payments without external support.

LGFVs borrow money in a murky area between government and corporate debt. While local governments claim LGFV debts are off-balance sheet, many observers see them as de facto government borrowing, with the implication that ultimately the central government will make good on defaults. The concern over LGFV borrowing stems from the intense increase in LGFV bond issuance since 2008 and the imminent pressure of upcoming debt repayments. A May 2023 UBS analysis of LGFV income statements shows that 65% of LGFVs can service the interest on their debts outright, while another 23% can with help from a subsidy from the local or central government. Their high reliance on land revenue presents a significant challenge as the property market continues to decline. Local governments are also under pressure following COVID-19 spending and revenue contractions from their own reliance on land revenue.

Does LGFV debt present a critical concern to the Chinese economy?

Historically, no LGFV has defaulted on public bonds, and a total collapse of the LGFV system would only come about through systemic abandonment from local and central governments. In the past, local governments performed a debt-swap, like the 2015-2018 swap that amounted to 12 trillion RMB. Banks have also provided refinancing or restructuring to struggling LGFVs. While total collapse is avoidable, reassessing the LGFV system is critically needed, and it would be a tedious and painful policy process that needs to stem from Beijing.

Beijing’s future policy options

The central government tightened LGFV oversight to mitigate risks, targeting offshore debt and signaling further structural interventions.

Expect debt relief strategies like swaps, refinancing, or restructuring to aid LGFV debt repayment. The central government, which has historically been seen as making good on local government debts, could mandate limited debt forgiveness as one way out of the financial morass.

Bank Relief: Much like for property developers, banks are extending and lowering interest on LGFV loans.

Local government bailout: Local governments, with central government assistance, likely will also protect LGFVs from serious debt default concerns, to maintain broader economic and investor confidence stability. This may include swapping LGFV debt for government bonds, providing subsidies, etc.